The Organization as a Network of ProjectsRecurrent and non-recurrent activities in an industry can be seen as “projects”. Whether we seek to improve the speed at which we manufacture products, install new equipment, organize shipments or file quarterly closing, we need the coordinated efforts of many different competencies. Deploying these competencies in a logical sequence is relatively easy. However, breaking assumptions about the way performances should be controlled and measured seems to be a true cognitive ordeal. The measurement of performances seems to be inextricably connected with a local, i.e. functional indicator while we all know that what matters is the global bottom line of the company. How do we come out of this seemingly irreconcilable conflict? We do it by asking ourselves what company functions are for, and uncovering the obvious truth that functions should house competencies, not power. Engineers, accountants, scientists, subject matter experts, should not be considered members of a “company function”. Rather, they should be seen as valuable competencies that can be deployed for the goal of the whole company. These resources, ALL the resources, should be available for whatever “project” the company needs to accomplish. What we are saying is that any company should be seen as a network of projects with the global goal of maximizing the Throughput of the company. The Critical Chain algorithm that Dr. Goldratt developed can be used to maximize the use of the finite resources of a company. As a matter of fact, this algorithm can be used to redesign the way any company works. Critical Chain becomes, then, much more than simply an algorithm to accelerate project completion; it is the vehicle to integrate, control and deploy the resources of the organization. Any organization develops very naturally as a network of interdependent components. What makes this network a system, as opposed to a grouping of efforts, is the definition (and the adherence to) a common goal. In other words, when people start collaborating for a common goal, the interdependencies necessary to achieve it can be very easily defined. The inherent conflict in any organization is whether or not to adopt a hierarchical structure. The hierarchical structure satisfies the need for control but artificially impedes the free flow of processes and communication. By recognizing that any organization is, in fact, a network of projects, an organization can maximize its potential and continuously improve. Intelligent Management and the Organization as a network of projects Different types of real organizations are dynamic systems that can be considered as complex networks, defined as a structure of interacting nodes and links connected to each other. In these organizations the greatest undesirable effect is ‘not to be able to work in a synchronized way’. Synchronization implies that every node of the network works toward the goal, and that the network/company goal is one only. We can think of a hierarchical organization as being made up of clusters whose hubs are not connected to each other. This type of organization can shift to a systemic network in which each node is attached to any other node through only a few links. The systemic approach in such a network would then support the creation of interdependencies in order to allow emergent properties to shorten the path toward achieving the goal of the network. How do we design such a systemic network? Such networks have to be built and designed through:

Only the goal of an organizational network can enable the proper identification of the logic with which the network has to be designed, the direction in which the network has to evolve, and the alternative paths to follow in case of ‘attacks’ to nodes due to the intrinsic variation of its processes. We can effectively manage organizations as complex networks through the Decalogue methodology. We do so by recognizing that the Undesirable Effects (UDEs) of an organization are in fact emergent properties. By understanding the emerging properties of an organization we can find many clues regarding the structure of the network, its interdependencies and the design of the organization. Such properties allow us to surface:

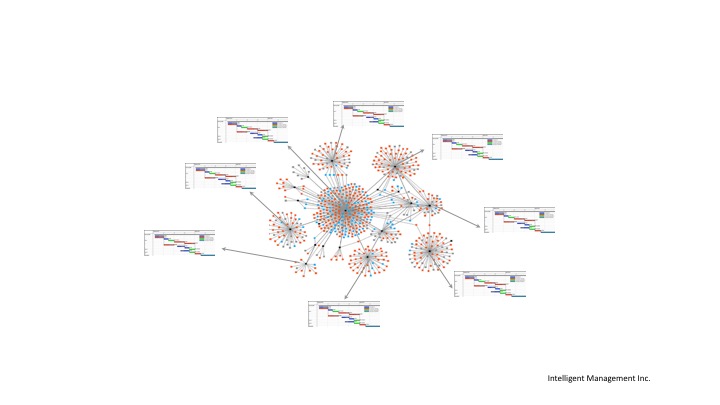

Only the goal of an organizational network can enable the proper identification of the logic with which the network has to be designed, the direction in which the network has to evolve, and the alternative paths to follow in case of ‘attacks’ to nodes due to the intrinsic variation of its processes. As a result, we are able to see that the achievement of the goal of the production network is limited by a few nodes that have less capacity than the others. Among such nodes we identify one, which we call the constraint, which has to be managed properly and protected from the intrinsic variation of the system. The constraint is a node whose finite capacity is the most limiting factor for achieving the desired goal of the production network. This node determines the speed at which the network generates products and, as a consequence, is strongly connected to the pace of sales. We can define the constraint as ‘the node with least capacity that has to be chosen strategically’ because it represents the measurement point of the business network. All other nodes are fully linked, within very few degrees of separation, to the constraint node in a way that increases the network cluster coefficient and supports the systemic design. From a Network Theory point of view, the constraint is the hub of the network and it is helpful to build the structure of the network itself around the constraint both in order to design properly its mechanics and to model the network in the direction of the goal. Hubs, the highly connected (few) nodes at the tail of the power law degree distribution, are known to play a key role in keeping complex networks together, thus playing a crucial role in the robustness of the network. They play the important role of bridging the many small communities of clusters into a single, systemically integrated network. The introduction of the concept of variation within a network enables us to look at the process of the output of any system and not solely at its single nodes. Every process made up of the work of many nodes is affected by an oscillation due to the interaction and the evolution of the network. Process Behaviour Charts display all these local interacting variations of the single nodes as a process and detect the specific limits within which the whole process can oscillate in a predictable way. This can be interpreted as a fluctuation of the predictability of the system. This fluctuation is called variation. The behaviour of processes within a network becomes non-deterministic in the case of interacting systems. The consequent emergence of new properties is an important characteristic to be kept under statistical control. At the same time, being aware of intrinsic variation allows us to monitor the development of the network, the statistical understanding of which helps us predict the emergent properties of the entire system. These two interrelated and cyclical observations are practically implemented by projects developed from the injections to the core conflict of the organization. Therefore, identifying the constraint and managing the intrinsic variation of the processes occurring in the company by using the methods of Statistical Process Control enables us to create a systemic network. The use of the algorithm from the Theory of Constraints known as Drum Buffer Rope (see synchronized management) and the intrinsic variability of the system enable the design of a scale free network made of hubs that connect nodes in a systemic way; buffers will take into consideration (and protect from) the intrinsic variation of the complex systems. Such a network, therefore, will drive its evolution toward a common goal. A feedback system will continuously feed the network through a few designated links that will spread the information throughout the nodes. The algorithm used in the Decalogue for managing projects is Critical Chain from the Theory of Constraints. Far beyond a technique, Critical Chain represents the embodiment of a vision of the organization based on pace of flow, people’s involvement, and great emphasis on quality. Quality, involvement and flow are the basic philosophical pillars of the systemic organization. Intelligent Management Inc. has now embedded the Network of Projects approach into a software for finite capacity scheduling of multi projects. See www.Ess3ntial.com SCHEDULE AN INTRODUCTORY CALL WITH US See our new book:’Quality, Involvement, Flow: The Systemic Organization’ |