Dr. Domenico Lepore, Founder of Intelligent Management Inc. and international expert in Quality and Systems Thinking for organizations, continues his series on the Standard of Innovation.

Why do we have Standards?

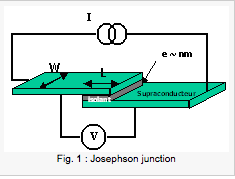

Standards are created to allow operationally defined quantities to be measured in a way that makes sense. After having defined “Volt” we need a “voltage standard” to allow us to measure, for instance, how much a measured voltage differs from the standard. In this sense, a standard is a reference point and everything is measured in terms of distance from the standard.

Standardization makes economic sense because it provides a common platform for the development of products and services that leverage the chosen standard. Any socket in any house in North America can safely power all appliances in North America because we have decided that the voltage drop is 110 volts at 50 Hz. “We” means the committee of experts that took upon themselves the burden of defining what seemed economically and technically sensible for a voltage of reference.

In recent decades the word “standard” has branched out to include the measuring of human activities, in particular management systems, and we have witnessed the flourishing of Quality standards, Safety standards, Environmental standards, etc. Their role in promoting what they were supposed to “standardize” has been somewhat controversial and largely misunderstood.

When it comes to management systems we, as organizations, seem to perceive a conflict between adopting and embracing a voluntary standard, say for Quality, and resisting it (openly or covertly). Knowingly or not, we feel that a “management standard” is in some way a burden, not a support; a cost, not a benefit.

Why do we feel that Standards can be a burden?

A technical standard is a reference point and the closer we get to that point the better we have performed. A management standard, instead, is a framework, a guideline, a set of principles. In other words, it is a source of suggestions (and, maybe, of inspiration) to define operationally what is best for your organization. As such, any management standard is not only voluntary but it can only represent a starting point, not a finishing line. A management standard must provide the operational definitions for the development of any improvement pattern.

Sadly, standards for management systems have been considered by organizations as “tests” for which they have to get a good grade so they can then flaunt its achievement as a ribbon for their excellence. Quality Standards have failed to promote “Quality”. Indeed, in 1982, Dr. Deming, the founding father of the Quality movement, declined the chairmanship of the ISO Committee 176 for the family of the 9000 standards as he saw it poised for failure. This must serve as a warning for all of those who wish to embark on the production of another management standard and its dissemination.

A Standard for Innovation

How about a standard for innovation? How can such a standard help to spread a culture of innovation instead of stifling it with the specter of “compliance”?

Innovation is not an optional; it is the very reason why companies exist. A company that slows down its “process of innovation” is destined to die. A reputable and useful standard therefore needs to:

1) Promote the concept that innovation is a process

Innovation is a process, not a winning post. You do not reach “innovation”; you create a network of processes, a system that sustains the generation of innovative products.

2) Emphasize the role that top management must have in providing an organizational framework to nurture innovation

As innovation is foundational to the prosperity of the organization (and its stakeholders) it must be the primary concern for the top management. They must promote innovation at the core of any business decision. In other words, a useful standard must prompt top management to think of innovation as a primary source for the economic success of their company, NOT as basic set of technical prerequisites that a functional director, “the Director of Innovation”, must fulfil to ensure compliance.

There are two more fundamental issues that a Standard for Innovation must promote, and we will look at these in the next piece in this series on the importance of Systems Thinking for Innovation.

See also:

Part 1 : A Word about words

Part 2: Imagination Does Not Equal Innovation

Part 3: The Interconnection of Leadership, Quality and Innovation

I agree with the benefits of technical standards, but I am haunted by my memory of the RS-232 “standard.”