The History of the Decalogue

“Western management has failed to understand cause and effect”.

W. Edwards Deming

There is no effect without a cause. This is the basis of the scientific method, and the aim of science is always to discover root causes. Without that knowledge, we are exposed to an array of ‘symptoms’ we are unable to decipher, predict, control, or prevent. In other words, we are in the Dark Ages.

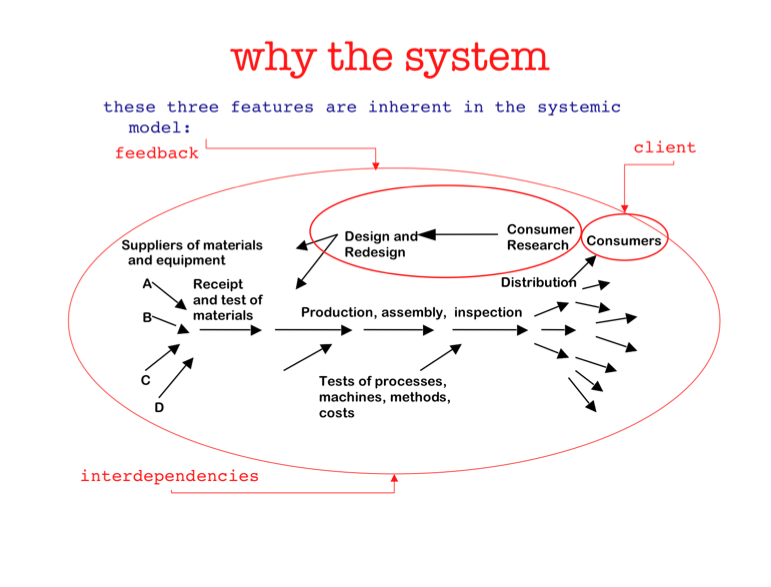

In contrast to a Cartesian and analytical view of nature, a systems-based approach within various disciplines began to emerge and establish itself in the 1940s. This way of understanding nature takes into account interdependencies among the various elements of a system.

The Decalogue is a science-based methodology that is founded on cause and effect logic and that views an organization as a system, i.e. a set of components that work together to achieve the goal of the system.

The Ten Steps of The DecalogueTM are themselves a system: they interact with each other and are incomplete without each other. A DecalogueTM system is organized around a constraint. Unlike a conventional hierarchy made up of vertical functions, the system is managed as a network of projects that are synchronized through the Critical Chain algorithm. Management has one purpose and one purpose alone: to subordinate all the processes in the system to the functioning of the constraint, i.e. the element that determines the pace of throughput, and to ensure that all company processes are reliable and predictable by understanding and managing variation.

This purpose can only be achieved by using an appropriate set of measurements to assess whether the system is achieving its goal. These are not the traditional measurements of Cost Accounting or GAAP. Product costing fails us in understanding profitability and prevents our understanding of true improvement opportunities in throughput generation. This almost universal approach in Western Management distorts the financial reality of a company by trying to imagine a fully absorbed cost of an individual product and then imagining an amount of profit called Gross Margin. Inventory is perversely seen as an asset. Rates of cash generation and speed are entirely ignored. These erroneous measurements can give a false sense of profitability or an incorrect sense of non-profitability, and hence lead managers to make the wrong decisions about what is creating true profit for the company. As Dr. Deming put it, “It is easy to count. Counts relieve management of the necessity to contrive a measure with meaning.”

The correct measurements for the DecalogueTM are those of Throughput Accounting that is designed to facilitate the generation of throughput. These are:

Throughput (T) : the pace at which the system generates cash through sales.

T = sales minus Total Variable Cost (TVC) associated with sales.

Totally variable costs (TVC) are part of the inventory that at any given time has to be present in the company in order for the product to be manufactured and sold. More in general, TVC represent the cash outlay for material and services connected with the sale of our products.

Inventory (I) : the material purchased to be transformed later into sales

Operating Expenses (OE) : the fixed costs and the investments needed for the company to generate sales.

The equations that link these quantities are:

T = Sales – TVC

Net Profit = T – OE = Sales – TVC – OE Cash profit = Net Profit – I

In this formula year after year we obviously consider Δ I

In other words, cash profit increases or decreases according to the fluctuation of the I that we need to keep in the system to perform sales.

History of The DecalogueTM: Dr. Deming

A leader of today must construct a theory for today’s world, and must develop an appropriate system for management of his theory. Why? Because without theory there is no learning, and thus no improvement – only motion. The theory that he requires is knowledge about a system and optimization thereof.

W. Edwards Deming

It took almost ten years to develop the ten steps of The Decalogue into an official and tested methodology. These ten years were founded on many previous years of preparation and study by its authors.

In the early 1990s, Dr. Lepore was asked by the training division of the Department of Trade and Industry in Milan, Italy, to design courses for Small and Medium Enterprises on the subject matter of Quality Management.

In his hometown of Salerno, Lepore had begun his work experience in a physics laboratory, completing his research thesis on non-linear dynamics in superconductors.vii The only child of a widowed mother, he was an atypical scientist. Witty and charismatic, he could fly a plane and speak fluent English just from having studied it. His passion for science was matched by a thirst for knowledge about management science. After his thesis, he joined a firm assisting Small and Medium Enterprises in buying new technologies and searching for business partners within the European Community. He was appointed Italian representative for the ISO [International Standards Organization] Technical Committee 176, Geneva, responsible for the development of the ISO 9000 family of quality standards, including quality standards for education (1993-96).

However, the economic and political conditions of Southern Italy offered no hope for a physicist with a precise interest in management and organizations. Milan was the only feasible alternative in Italy. The first year was especially tough; the Gulf crisis had frozen all job opportunities, and Lepore worked as a supply teacher of physics in a high school. One year later he was hired by a special agency of the Department of Trade and Industry.

Dr. Lepore and Dr. Deming

As he worked on managing and creating training programs on Quality, Lepore studied the management philosophy of Dr. W. Edwards Deming, a statistician and physicist. He was struck by the power of Deming’s message and the scientific rigor of his work. Deming’s theory was strong in its own right, but far from remaining a theorist, Deming had taught Japanese industrialists and engineers what they needed to know to rebuild their country after World War II. The solidity of Deming’s background as physicist and statistician was informed by a deep understanding of people’s needs in order to work productively and be fulfilled in their jobs.

Through Deming, Lepore understood how a science-based approach could revolutionize the way an organization is shaped and managed. It was clear to Lepore the physicist that a mechanistic vision of a company as a conglomeration of separate departments and individuals was a vision that lagged behind the knowledge that science had gained of nature by many decades. Deming’s approach to management, instead, was systemic, seeing an organization as a system that encompasses customers and suppliers.

Deming viewed the organization as a system made up of the processes that constitute the work of the system, transforming input into output. This becomes clear through the use of flowcharting, a fundamental means for gaining and reinforcing this view of the organization. When a company flowcharts all of its processes, it shows how these processes cut across traditional separations. It allows people to see exactly how their process contributes to the system, and it provides managers with the knowledge they need to improve processes, and where to place appropriate measurement points.

Having a solid grounding in statistics, it made total sense to Lepore that central to Deming’s philosophy was the understanding of variation. Inspired by the work of statistician Walter Shewhart, Deming had recognized the profound importance of understanding variation, and the crucial need to be able to distinguish between its special and common causes. Variation, like entropy, exists. It affects all human, natural and mechanical processes: nothing repeats itself exactly the same way twice. All variation is caused. While it is ‘difficult if not impossible to link common cause variation to any particular source’,viii because it is the plurality of factors that creates the amount of variation inherent in any system, it should be possible to track back the special causes.

In the Deming approach, knowledge and understanding of the system is gained by using Statistical Process Control to monitor variation in the behavior of processes and understand whether or not they are stable. Far from being a mere tool, SPC is a way of thinking. It gives managers the information they need to truly understand what is happening in the system they are running.

Thus, as Deming explains, the essence of management is prediction, and this can only be achieved through a thorough knowledge of how the system operates. Only then can managers anticipate the effects of any actions they take on the system. Indeed, the malfunctioning of an organization is almost entirely due to the misunderstanding of the system by the management.

Lepore found Deming’s writing both enlightening and inspiring. What was needed was a new kind of manager. Someone who based their career on knowledge. The personality cult of certain ‘successful’ managers was blatant nonsense, and indeed harmful. A firm scientific approach, a solid theory, and the patient ability to implement it were what were required.

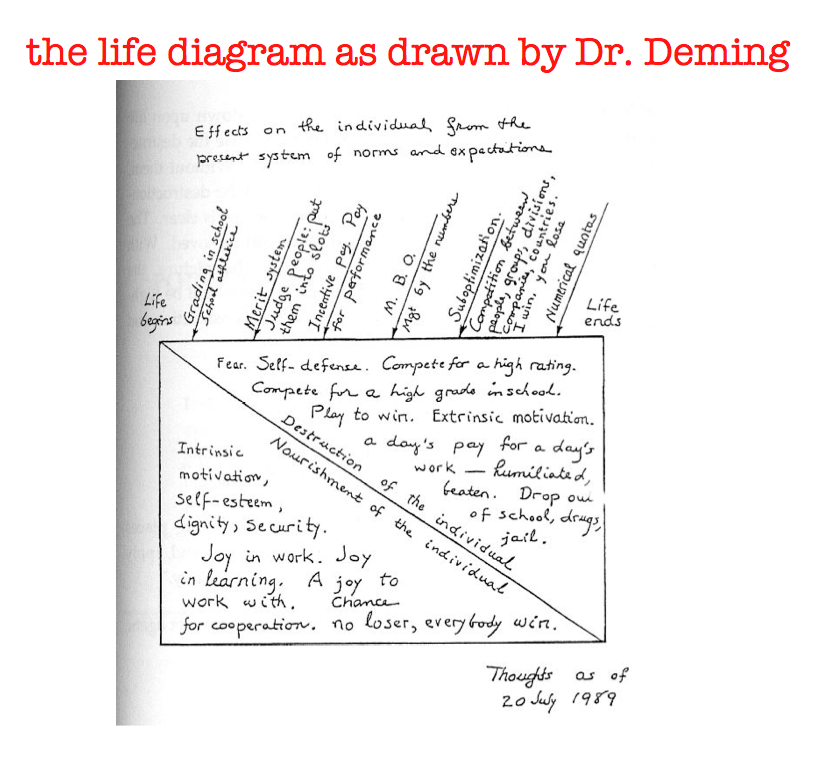

“Traditional appraisal systems increase the variability of performance of people. The trouble lies in the implied preciseness of rating schemes. What happens is this. Somebody is rated below average, takes a look at people that are rated above average; naturally wonders why the difference exists. He tries to emulate people above average. The result is impairment of performance.”

Lepore began piecing together the DecalogueTM during his studying and teaching years with the Department of Industry. Profound study and direct contact with businesses were the essential humus for its development. Ironically, he was working within an organization that itself practiced many of the approaches Deming had condemned, such as annual performance reviews. Indeed, Lepore received very few pay rises during his working years there, but he was grateful for the opportunity to study and develop an effective methodology.

Deming revealed the fallacy of looking at the performance of individuals and ‘rewarding’ them or ‘punishing’ them on the basis of arbitrary targets. It is never the worker that is the problem, but the system within which the worker operates. Hence the need for management to have the tools to truly understand the behavior of processes within the system which are either statistically in control or out of control. When they are in control the system is predictable and what it produces is predictable. An out of control system may produce ‘good’ results but in a totally unpredictable way. A peak in sales this week could be followed by a trough next week. Management’s job is to understand the causes and act on the system with knowledge. Any other kind of action results in tampering, which can only introduce further variation into the system and increase unpredictability.

It takes much more than tools and techniques to achieve a systemic organization, it requires real knowledge and a mindset that differs radically from that of the early days of industry. A system does not require heroes to put out fires. It requires continuous learning and relentless continuous improvement. This can be achieved by following the Deming cycle of Plan, Do, Check, Act.

Necessary but not sufficient: Deming and the Theory of Constraints

In his early work teaching and guiding enterprises in northern Italy, Lepore ascertained on the field that Deming’s philosophy was precisely what organizations needed to maximize their performance and continuously evolve. The problem was the difficulty companies experienced in translating the philosophy into day-to-day practice. Deming’s legacy was a complete system of knowledge, but without a precise set of instructions. Companies floundered in their attempts to make it happen.

Lepore was introduced by a colleague to the work of Dr. Goldratt and was struck by the simplicity and power of the Theory of Constraints (TOC). He traveled to the UK to meet Oded Cohen, Goldratt’s longest-standing partner. The meeting was to change the course of his future professional life. He began to learn the Theory of Constraints in depth, tutored and encouraged by Cohen.

Cohen was the partner of the Avraham Goldratt Institute responsible for Southern Europe. An Industrial engineer with an MSc. in Operations Research from the Israeli Institute of Technology in Haifa, Israel, he had worked alongside Dr. Goldratt since the early ‘eighties, and helped develop the Thinking Process Tools. He was the designer of the Management Skills Workshop, the course Lepore attended on the first of many visits to the Goldratt Institute in Maidenhead, UK. Recognizing Lepore’s affinity with the Theory, Cohen supported him with training and mentoring.

TOC is also a systems-based approach to management: it maximizes the throughput of every organization by identifying the constraint (Throughput is defined as the pace at which a system generates cash) and subordinating all the processes in the organization to the performance of the constraint chosen. TOC uses a series of logical tools called “Thinking Process Tools” (TP Tools) to identify problems and design, plan and implement solutions and strategies. TOC as a body of knowledge contains a series of applications used successfully worldwide for many years to manage production, project management, new product development, marketing and sales.

Lepore began to infuse his work on Quality with the Theory of Constraints. He realized that TOC was the missing link in Deming. It was a systems-based approach, as was Deming’s, but Lepore saw clearly that the TP Tools and the applications from TOC could transfer powerfully and rigorously the message of Deming to organizations. Not only was it a perfect fit philosophically, it provided the practical tools to put the philosophy into action. The Thinking Process Tools were the logical tools that managers could use to transition their vision into a working reality, down to the most minute detail. The combination of Deming and Goldratt was the beginning of a new theory and practice of systems thinking applied to organizations. Lepore realized that not only were these two systems- based theories complementary, they reinforced each other. The complexity of Deming’s theory could be applied more readily by managing the organization through the focusing process of the constraint. Moreover, the Thinking Process Tools provided the means for an effective and systematic implementation. The collaboration between Cohen and Lepore was to lead to a firm friendship and the development of a new management methodology.

When Lepore returned home from a week of training in Maidenhead in 1995 he was exhausted but exhilarated. Using the TOC Thinking Process tools, and under Cohen’s expert supervision, Lepore constructed a Future Reality Tree that would guide him in setting up his own consultancy company. In 1996 he founded MST (Methods for Systems Thinking) to enable organizations to develop continuous improvement programs based on Deming’s teachings and the Theory of Constraints. His English wife, Angela, assisted him in founding and running the company while continuing to teach and translate. The couple had no capital to start the business, but the bank granted them a small overdraft. Overheads were low as the company operated from their small rented apartment in Milan. The business gradually grew and moved into a tiny office in the Bicocca Business Incubator. The small MST team became expert in Quality Certification projects, and in improvement projects in a much wider sense for a broad range of companies, from nursing homes to multinationals. Clients achieved astonishing results, reducing lead-time, improving performance and increasing sales by developing breakthrough solutions. Lepore began delineating a complete approach to transforming companies into thinking systems.

MST doubled its turnover every year, and Lepore systematically ploughed profits into developing and testing his approach to organizational science. He resisted the temptation of a better lifestyle, and continued to reinvest, inspired by the vision of a new and more complete methodology. The MST team grew, and a larger office was found in central Milan. MST worked with a broad range of organizations: small, medium and large manufacturing companies both public and private, service companies, not-for-profit organizations, academic institutions and government bodies. The algorithm for a complete transformation of an organization into a thinking system was becoming increasingly clear, and was repeatedly tested and refined. The shift from Quality Systems to turnaround implementations became inevitable.

In 1998 Lepore and Cohen met with Larry Gadd, President of North River Press and publisher of all of Goldratt’s bestseller books. Gadd’s unique insight revealed the potential and importance of combining Deming and Goldratt as a methodology in its own right. The transformation algorithm was made up of ten steps and was therefore officially named ‘The Decalogue’TM. Gadd gave his encouragement and support, and published Deming and Goldratt: The Decalogue (North River Press, 1999). It was the first book he had agreed to publish dealing with the Theory of Constraints that was not written by Dr. Goldratt himself.