Just ONE point of your organization can help you organize and manage your whole company. It’s a strategically chosen constraint. Everything else is connected to it so you can focus on ONE area instead of trying to focus on ALL areas – something that is impossible and a great time waster.

Step Five of the Decalogue Method is: Manage the constraint (protect and control the system through buffer management)

As all these aspects of management are new to the majority of entrepreneurs, leaders and managers, let’s recap on the role of the buffer. (Let’s remember, also, that a constraint is NOT a bottleneck. See ‘Constraints and Bottlenecks: You Need to Know the Difference‘ )

A strategically chosen constraint is what allows us to manage the organization as one, whole system. In some companies, for example, this could be a group of specialized resources, in some other companies it could be a particular phase of production. Given its importance, both strategically and operationally, we clearly need to be able to protect it. This protection is provided by the buffer and by its management.

What is a buffer? Individual processes in our system exhibit variation; two or more together do too and this is called covariance. The effect of covariance is a cumulated variation that can result in any sort of combination of these variances. Regardless of how little individual variation the processes of the system have, we do need a mechanism to protect the most critical part of our organization, the constraint.

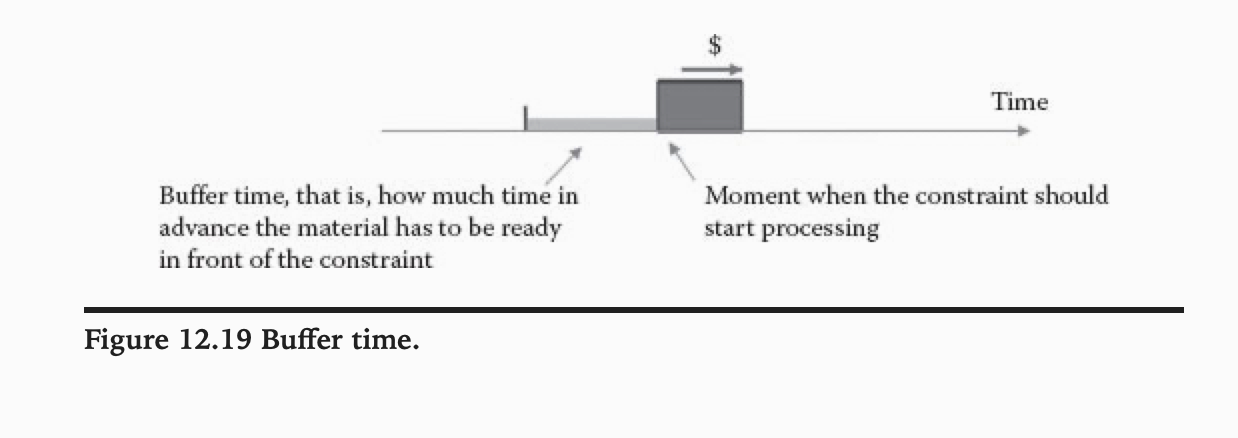

A buffer is a quantity of “time” that we position in front of the constraint to protect it from the cumulative variation that the system generates. Simply put, by synchronizing the processes that deliver the output of our organization, we ensure that everything the constraint must work on gets in front of it “one buffer time ahead.”

Is there a precise and unequivocal recipe to size the buffer appropriately? No, and it doesn’t matter. If you understand control charts, the sizing is fairly obvious. The real importance of the buffer is not in the protection from disruption, certainly not an irrelevant issue, but in the possibility to exert control over the functioning of the whole organization: if our processes are all predictable, then we can truly use the buffer as a mechanism to gather succinct, effective, and comprehensive information about the “state of synchronization” of our company. Indeed, if we monitor the buffer with the use of a control chart, then the control becomes real insight, and that is the goal of management.

A new kind of control

Managing the buffer of our constraint entails a Copernican shift in the way we mean control because it prompts decision makers to rely on understanding and knowledge rather than hunches; it forces them into leveraging arguably esoteric statistical studies instead of salt of the earth accounting; it constrains the unbridled vibrancy of managers into the straightjacket of rational thinking. As a result of those considerations, over the decades, in spite of its effectiveness, many of the repeated attempts to introduce buffer management to top management have failed.

Subordinating to the Constraint: Buffers and Variation

For the constraint to be able to function effectively, we need to “subordinate” the rest of our system/organization to it. What does that mean?

Subordinating means making sure the system acts in such a way that the constraint is allowed to work flat out without interruptions. Subordinating means having an action plan for the resources, that is, a scheduling that takes into account the presence of the constraint (we must never starve the constraint).

By definition, every minute lost on the constraint is lost forever, with an evident loss of profit. Once we have identified/chosen strategically the constraint, we create a detailed planning for it bearing in mind two things:

- The constraint must work on the right product mix (what makes sense economically for us to produce bearing in mind the amount of constraint time the product or service absorbs)

- The constraint must work as close as possible to 100% of its capacity.

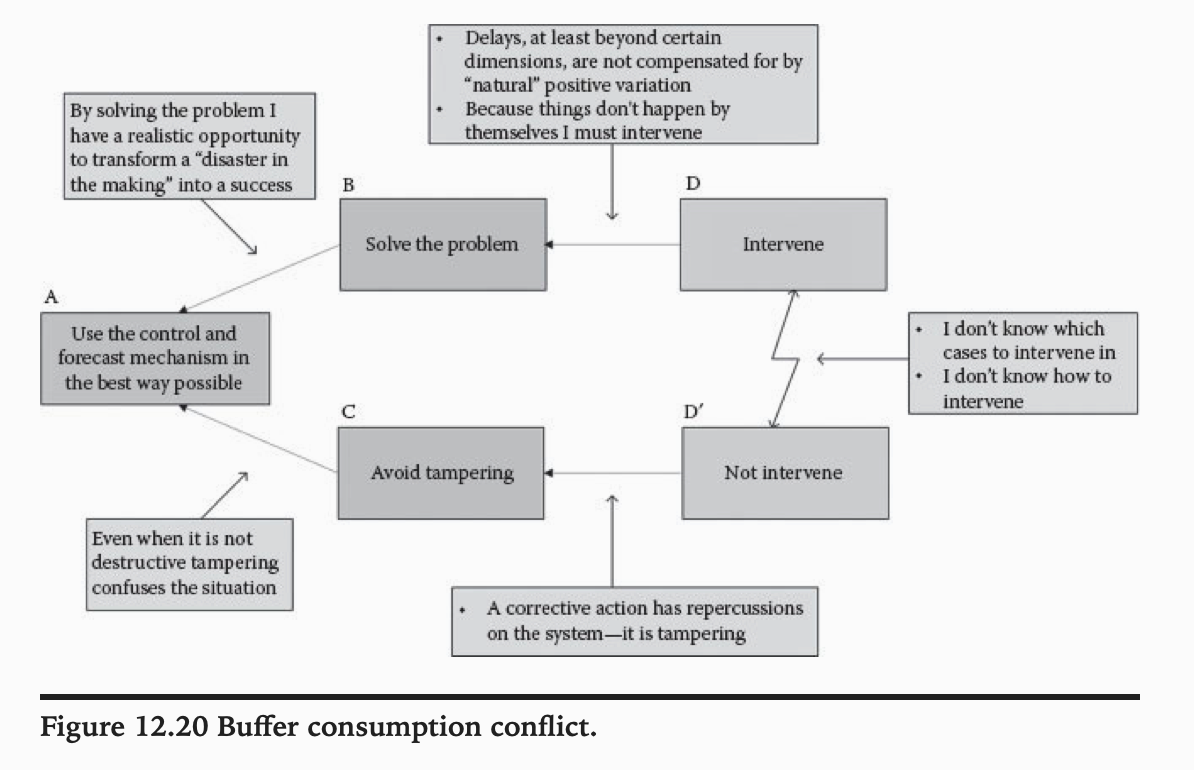

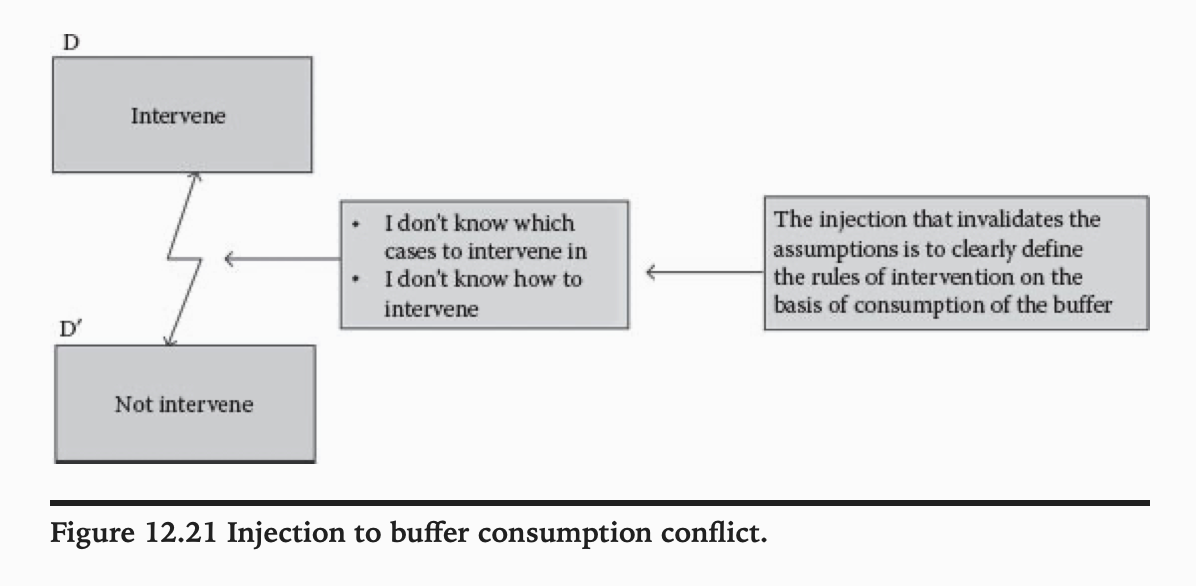

In the case of buffer consumption, managers find themselves faced with a basic conflict: intervene on the system versus not intervene on the system.

The traditional Theory of Constraints (TOC) approach divides the buffer into three zones and suggests different behaviors according to the zone of the buffer that has been “emptied.” The buffer will “empty” out or “fill up” depending on whether tasks or operations are completed early or late in respect with the scheduling.

However, as we said, the ability to predict is the essence of management, and only if we are able to foresee the outcome of our actions on the system can we take decisions that anticipate the development of events and therefore have more control over them. In the traditional TOC approach, we “react” to a situation; when the buffer is emptied, we react. This is not the Decalogue approach.

We have defined a stable system as one that produces predictable results so, the question here is: is the system stable? In the Decalogue approach we use Statistical Process Control (SPC) to monitor and control the system. In our approach to buffer management we use SPC to monitor, control, and improve the way the constraint is exploited and, in general, to size it adequately.

What we do is to size the buffer, and monitor the oscillation of its consumption to see if it is in control. If this is the case, independently of how much it is emptied, we do not have to take any action. On the other hand, even if the buffer is not emptied substantially, if the oscillation of the consumption is not in control we have to act on the system to bring it back in control because, in this case, we cannot predict what will be the consumption in the future.

In conclusion, if the processes that impact the buffer are not stable, we cannot define the amount of protection needed (sizing the buffer).

The buffer acts as a means of control only if the processes of the system are in control and buffer consumption oscillates stably with an upper limit that is inferior to the maximum width of the buffer.

The Buffer and Performance Indicators

The Theory of Constraints offers us some measurements that allow us to understand how the whole system is performing. (See How to Make the Best Decisions for Your Company and Measure What Matters – A Systemic Approach to Management Part 3)

If we take manufacturing as an example, if a semi-finished piece stays in front of the constraint for more than a buffer of time, the system accumulates Inventory Dollar Days (IDD), that is, the system holds too much inventory in relation to what it is strictly necessary to protect the constraint.

In other words, if we look at the control chart of the buffer consumption, and the width of the buffer is greater than the upper control limit, then there is more protection than necessary, which means excess IDD. However, protection is not needed only on the constraint. We also need a buffer to protect the delivery date of the product.

If the buffer that protects the delivery date is consumed completely, the delivery is delayed and the system accumulates Throughput Dollar Days (TDD).

In conclusion, TDD is a measurement of performance related to the delivery date: if the buffer in front of the constraint is completely consumed (i.e., a semi-finished piece is not available when the constraint should process it), the deliveries are not automatically delayed, because there is still a protective buffer of finished products.

On the other hand, too much buffer of finished products becomes IDD: if this excess repeats itself in a predictable way (see the buffer control chart), then the buffer can be reduced.

Since a smaller buffer means a shorter lead-time, then we know we can count on a commercial opportunity and the possibility to make more competitive offers to the market.

Try it for yourself

Think of your own organization. Do you have a way of knowing how the whole organization is performing? Do you have a way of measuring the performance of the whole organization? Is there a strategic constraint you can think of in your organization and do you have the protection capacity available to ensure that it is always working as smoothly as possible? Do you have a way to predict the way your organization will perform in the future?

See Part 11 of this series: Leading and Managing change Effectively: It’s a Process that Includes You

PREVIOUS POSTS IN THIS SERIES:

Radically Improving Organizational Performance – A Systemic Approach to Management Part 1

Leadership for Complex Times – A Systemic Approach to Management Part 5

Working with Variation to Support Good Decision Making – A Systemic Approach Part 7

Why Your Organization’s Constraints Are the Key to Success – A Systemic Approach Part 8

Leave a Reply