In the previous post we looked at interdependencies and establishing the goal of the system.

In order to steer our system in the right direction we have to know how to make the right decisions. To do this it is essential that we be capable of assessing to what extent our system is achieving its goal. In other words, we have to be able to measure the system. For this we need to establish:

- The units the system uses to measure its progress toward the goal;

- A set of measurements suitable for assessing the impact of every local decision on the goal of the system. This in itself forms an adequate support tool for decision-making.

Before we establish in detail the measurements we need, let’s clearly focus on the significance of the decisions we must make to manage the system, and the direction we should take.

A leader/manager’s job is to coordinate the efforts of all the components of the system in order to achieve the pre-established goal. We call this process optimizing the system. Everything that does not optimize the whole system will inevitably lead to losses. Even if we have the best human and technical resources available, if they do not work as a system then our organization will lag behind other companies that may not have our ‘‘all star’’ team but that are managed and operated systemically.

People have to be allowed to interact in such a way that they can see that it is not the sum of their individual efforts but their coordinated activities that produce the best results.

Leaders/managers have to abandon the idea that the system’s performance can be improved by means of the isolated efforts of single functions. For Deming, a leader is a perennial learner, constantly engaged in the improvement of the conditions in which their people interact. In The New Economics, Deming points out that managers have to make the best use of people’s abilities and inclinations. A group of four people (A,B,C,D) can work in this way:

A+B+C+D (sum of individual abilities)

Or in this way:

(AB)+(AC)+(AD)+(BC)+(BD)+ . . . +(ABC)+(BCD)+

The brackets represent interactions between people in pairs or groups. These interactions can be either positive and helpful, negative and harmful, or zero, producing a net outcome which is bigger or smaller than, or equal to, the individual contributions. As Deming says:

‘‘One of management’s main responsibilities is to know about the existence of interactions, to perceive how they originate, then to change negative and zero interactions into positive interactions.’’

In a system, the result achieved by a single individual or function makes sense only in terms of the extent to which it affects the overall result—achieving the goal.

If we continue to use a set of measurements that encourages individuals and single departments to optimize their local performance, we undermine the shared vision we established before. It is the strength of this shared vision that increases daily the level of cohesion among people, keeping their actions in line with the common goal.

Now that we have determined the direction our decisions have to go, optimizing overall performance, let’s go on to establish the measurements we need.

What measurements do you need to make the best decisions for your company?

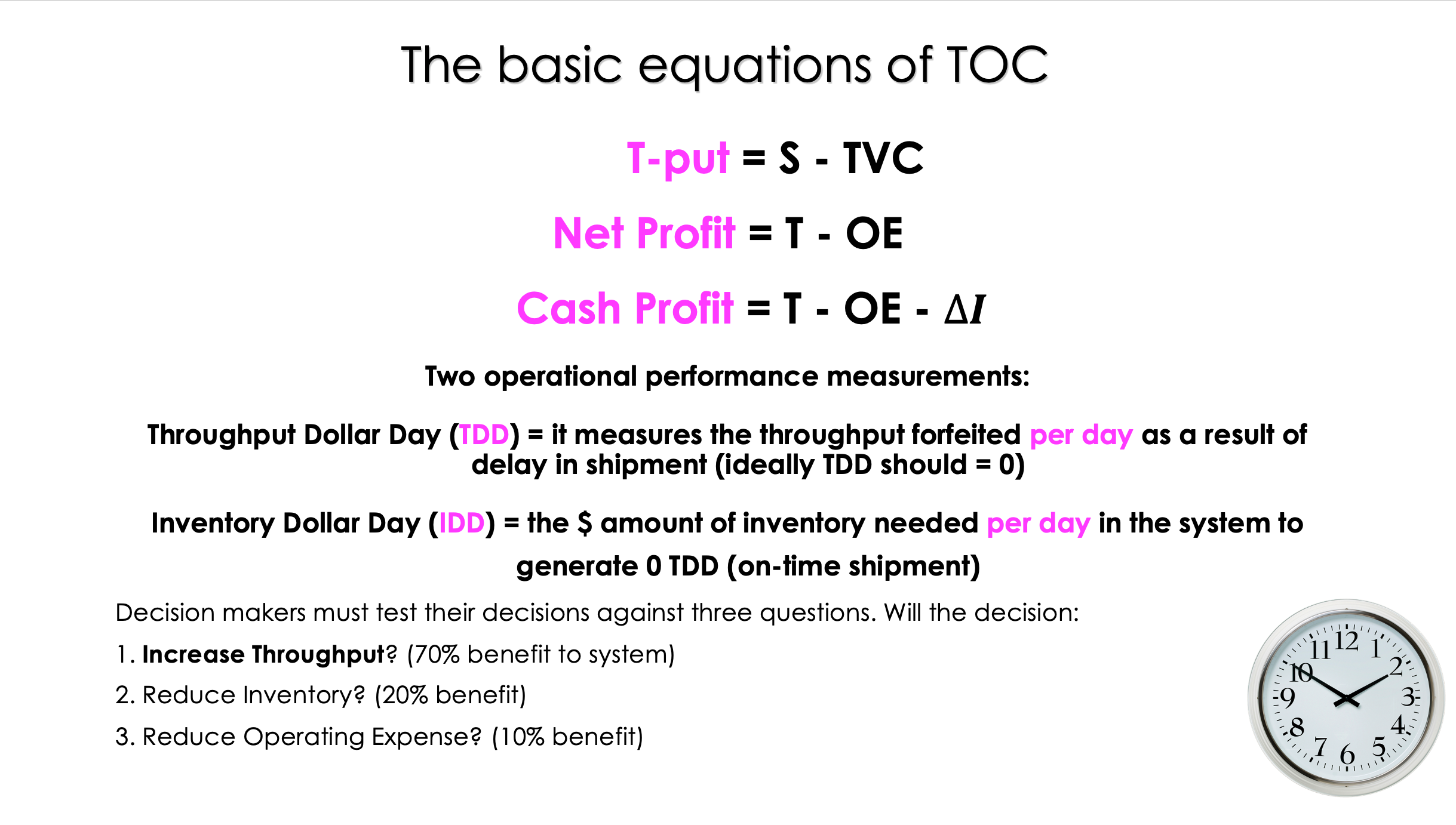

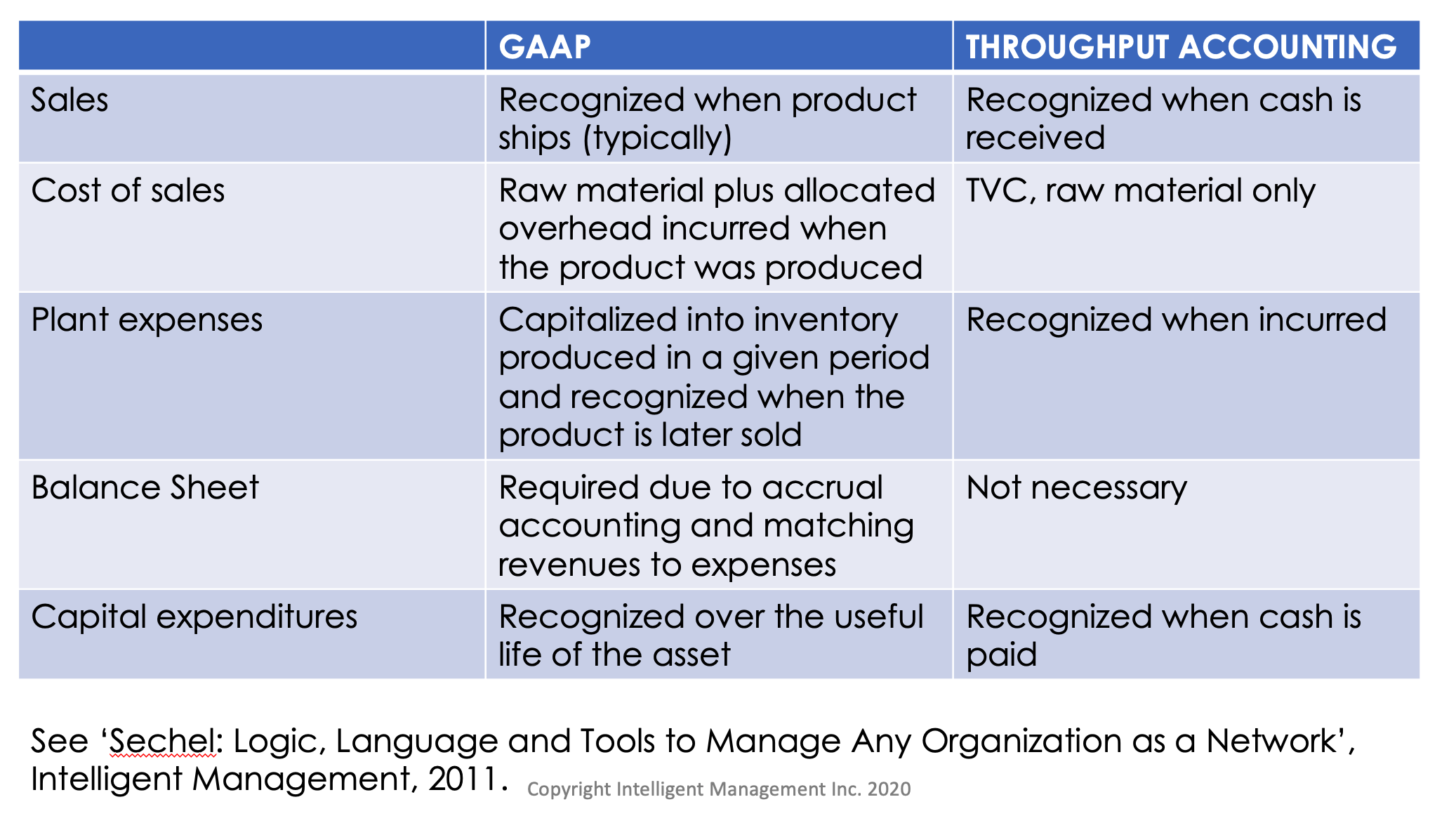

Without a goal there is no system and without clarity on what to measure in the system and how to measure it, talking about a goal becomes lip service. GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) accounting utilized to support managerial decisions is the enemy number one of productivity. EBIT (Earnings Before Interest and Tax), EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization), EPS (Earnings Per Share) and any form of GAAP-derived measurements totally miss the point of what a company should strive for. If the goal of a company is connected in any way with making money, then all we need to know is explained in the Theory of Constraints (TOC) and is the following:

- What comes in (Sales)

- What goes out to purchase materials and services that go into the products we sell (TVC, totally variable costs)

- What we need in order to make the system function (fixed costs + investments), operating expenses (OE)

- The inventory (I) we need to keep in the system to ensure that we always have enough “material” to produce and ship

These basic variables are connected in the following way:

Sales minus TVC = throughput (T); T minus OE = net profit; T minus OE minus I = cash profit, the physical money we see in the bank account before tax. Indeed, from year to year, I becomes Δ Delta I. Throughput is overwhelmingly more important than inventory and OE because it can potentially grow far more than OE and I can be reduced only so much. Sadly, the whole GAAP effort revolves around “understanding OE” with devastating effects on decision making. Let us say this clearly: the industrial world is where real wealth can be created and industry needs to learn how to measure its performances based on T, I, and OE. Banks, the stock market, financial institutions, and the guild of accountants must understand that their job is to support true wealth creation by fostering in industry the pursuit of these measurements instead of thrusting upon them anything different.

Nearly 30 years ago, Dr. Goldratt explained these simple concepts and all the financial and industrial catastrophes we have experienced in the last 25 years are, directly or indirectly, the result of not having understood them. Throughput is the most powerful way to link the industrial and the financial worlds and the performance measurements that go with it provide a whole new and meaningful scope to the endeavors of the accounting profession.

It is also critically important to measure how the system performs in its effort to deliver to customers. We can have a pretty good handle on it by measuring the on-time delivery and assigning a dollar value to any delay, we call it T$D (throughput $ day). The longer the delay, the higher the T$D. Similarly, we want to know how much cash we keep trapped in inventory to achieve an optimal, ideally zero, T$D, and we call it I$D (inventory $ day).

Let’s look at an example

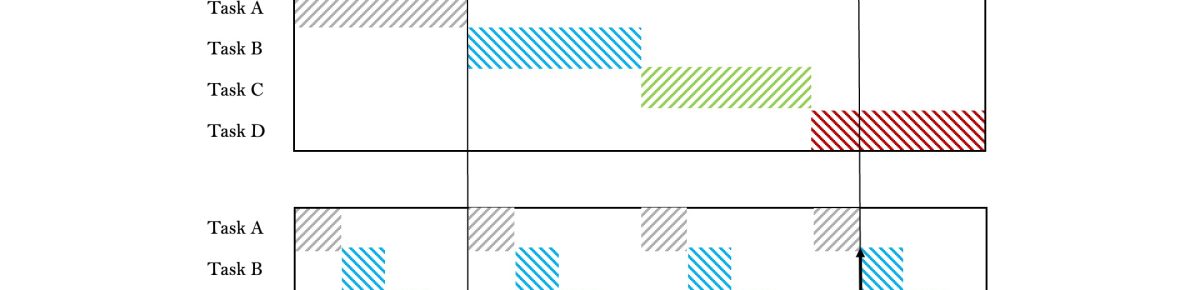

A manufacturing company in Italy produces automotive components for a big car manufacturer. It is Friday afternoon and an order that is needed for Monday morning in Sweden is not completed yet. The production manager has to make a decision: whether to call people to work on the weekend and use a private airplane to fly the components to the customer, or to carry on with the regular work and ship it late on Tuesday, using their regular method of shipping which is rail and boat. The weekend work and the private plane increase the operating expenses. Concurrently, if they do not ship on time, then immediate Throughput is endangered as the income from the customer will be delayed, they may be subject to a penalty (which reduces income) and their vendor rating will go down, which may jeopardize future orders both from this company and from other companies.

By looking at this problem, we can expect to be in continuous dilemmas about the trade-off between Throughput and operating expenses and inventory. The dilemma springs from the fact that Throughput brings money into the system, whereas investment and operating expenses are taking it out. But there is more to it. There is the issue of timing. The money that is used by OE and I is concurrent. It is here and now, while Throughput lies in the future. This time delay introduces nervousness into the system.

Leaders/managers find themselves dealing with a serious conflict. Undoubtedly, in order to make the right decision, they must increase the system’s Throughput. To do so they must take action aimed at increasing sales. On the other hand, in order to make the right decision they must reduce the amount of money used by the system, i.e., reduce I and OE.

The sensation is of being in a game you can’t win. Whatever decision we make we are bound to lose. The dilemma springs from the simple fact that miracles don’t exist. The experience of this dilemma can leadLeaders/managers to paralysis.

Using the Theory of Constraints to become confident you can make the best decisions for your company

The paralysis is caused by not being able to decide what is better. The solution to this problem is to have a simple, clear-cut mechanism for making these decisions—a way of assessing the impact on our three measurements, T, I and OE. (Throughput, Inventory and Operating Expense.)

The Theory of Constraints has a simple way of analyzing this and determining whether an action or a decision brings the system closer to its goal or takes it farther away. In for-profit organizations there are two relevant relationships between the three measurements: T, I, OE.

The difference between Throughput and Operating Expense reflects the amount of money left in our hands after deducting the money we pay for operating expenses from the money generated by sales. We must ignore the traditional measurements of cost accounting and consider the difference between T and OE as a close and accurate approximation of the Net Profit.

If the difference between Throughput and Operating Expense is positive, then the impact of the net profit of the system will be positive, irrespective of the type of financial reporting the system is subject to. This is an important point as, in many cases, leaders/managers have difficulty with the connection between their actions and the bottom line results of the company. The only measurements leaders/managers should use for decision-making are T, I and OE.

Why measure?

We have to ask ourselves why we need these measurements at all. To answer this question we have to go back and define a leader/manager and his or her role:

- A leader/manager is a person who is responsible for the performance of an area in a system.

- A leader/manager’s role is to constantly improve the performance of the area under his or her responsibility.

In order to ensure that the area performs well, the leader/manager has to take actions and make decisions. Without a system of measurement the leader/manager has no guidelines for making good decisions and cannot succeed. A useful measurement is one that provides the bridge between decisions and the bottom line performance of the system. The TOC measurements build that bridge.

There is no “reconciliation” possible between GAAP-driven and Throughput-driven financial performance measurements. What can be of use is the following table that makes evident how the different paradigms that inspire the two approaches manifest themselves.

Try it for yourself

When you next have to make a decision, ask yourself if the result of that decision will:

- Increase Throughput (70% benefit to the system)

- Reduce investments and inventory (20% benefit to the system)

- Reduce operating expenses (10% benefit to the system)

See Part 4 of this series How to Drastically Improve Company Results through Healthy Interactions

PREVIOUS POSTS IN THIS SERIES:

Radically Improving Organizational Performance – A Systemic Approach to Management Part 1

To find out more about ten guided steps to a systemic leap for your company, contact Angela Montgomery at intelligentmanagement@sechel.ws

SCHEDULE AN INTRODUCTORY CALL WITH US

Intelligent Management works with decision makers with the authority and responsibility to make meaningful change. We have helped dozens of organizations to adopt a systemic approach to manage complexity and radically improve performance and growth for 25 years through our Decalogue management methodology. The Network of Projects organization design we developed is supported by our Ess3ntial software for multi-project finite scheduling based on the Critical Chain algorithm.

See our latest books Moving the Chains: An Operational Solution for Embracing Complexity in the Digital Age by our Founder Dr. Domenico Lepore, The Human Constraint – a digital business novel that has sold in 43 countries so far by Dr. Angela Montgomery and ‘Quality, Involvement, Flow: The Systemic Organization’ from CRC Press, New York by Dr. Domenico Lepore, Dr. .Angela Montgomery and Dr. Giovanni Siepe.

Leave a Reply