Dr. Eliyahu Goldratt’s main contribution to the theory of management has been to point out that any system is limited toward its goal by very few elements, the constraints. If we identify them we can manage them following the focusing steps that he developed. The Decalogue method leverages the intrinsic stability of a Deming-based system and suggests that the constraint can be “chosen” (one constraint) instead of being identified. In other words, we can always decide which constraint it is strategically more convenient to focus on as a leverage point and build the system accordingly. However, this requires a system made of low variation processes; this is why we can safely design our company around a strategically chosen constraint. Instead of cycling the five focusing steps of TOC—(1) identify the constraint, (2) exploit the constraint, (3) subordinate to the constraint, (4) elevate the constraint, and, if the constraint has moved, (5) go back to step (1)—we can make the system grow by appropriately choosing the constraint and sizing the capacity of all the feeding/subordinating processes coherently. Again, this is possible only because the variation in the system is low. This is Step Four of the Decalogue method.

Let’s look at how this works.

The word constraint may sound negative but it is very useful. This is true for two precise reasons:

- We need a constraint to facilitate the synchronization of the different processes in the system (the constraint is the element that dictates the pace at which value is generated).

- We need a constraint because an “unbalanced” system is more resilient and it is more easily managed when the impact of variation is taken into account

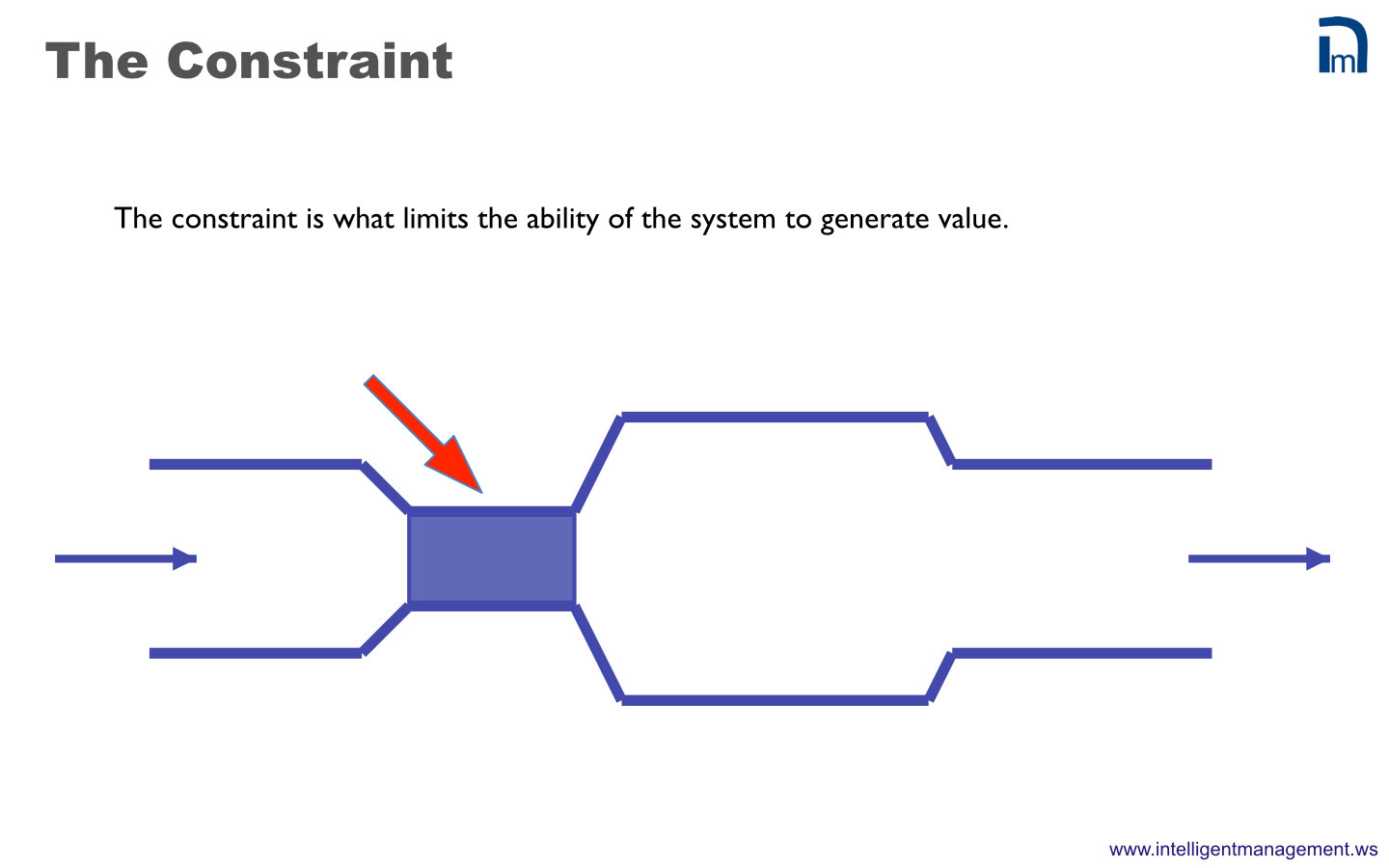

The constraint is what determines the pace/speed at which a system generates units of its goal. In for-profit companies, the units of the goal are linked to the generation of cash profit (value).

A system that is unbalanced around its constraint is like a tube with one section that is narrower than the rest: there is one phase/process/group of resources with less capacity than all the others.

Why do we manage a system through its constraint? It is because an unbalanced system is simpler and cheaper to manage. In an unbalanced system everything revolves around the constraint phase, and a detailed plan is necessary for this phase only. This schedule allows us to manage the whole operation. Reducing (global) variation in an unbalanced system means concentrating on and investing in the constraint phase only, not every single part of the process.

Markets that are stable and repetitive over time, both regarding quantity and product mix, are not very common. That is why following the variation in demand is very difficult. By unbalancing the system around its constraint, we can achieve a flexibility that is much more manageable because the problem of sizing capacity (and making any changes) only concerns the constraint and not every phase of the process.

Let’s repeat this crucial concept. The constraint determines how much the system can accomplish. Even if we choose to ignore it, this is still the case because every system has a constraint. Instead, when we consciously work with the constraint, we can leverage it to obtain the maximum throughput our system is capable of producing.

Protecting and Controlling the System: Buffer Management and the Constraint

The performance of our system is ensured by its predictability but we need a mechanism to protect it and control it. This is provided by the buffer and by its management. What is a buffer? Individual processes exhibit variation; two or more together do too, this is called covariance. The effect of covariance is a cumulated variation that can result in any sort of combination of these variances. Regardless of how little individual variation the processes of the system have, we do need a mechanism to protect the most critical part of our organization, the constraint. A buffer is a quantity of “time” that we position in front of the constraint to protect it from the cumulative variation that the system generates. Simply put, in synchronizing the processes that deliver the output of our organization, we ensure that what has to be worked on by the constraint gets in front of it “one buffer time ahead.”

Is there a precise and unequivocal recipe to size the buffer appropriately? No, and it doesn’t matter. If you understand control charts (see Part 7 of this series) the sizing is fairly obvious; if you don’t, you have bigger problems to cope with.

Controlling the whole organization through the Constraint

As Dr. Deming would most probably comment: “Let’s go back to serious business.” The real importance of the buffer is not in the protection from disruption, certainly not an irrelevant issue, but in the possibility to exert control over the functioning of the whole organization: if our processes are all predictable, then we can truly use the buffer as a mechanism to gather succinct, effective, and comprehensive information about the “state of the synchronization” of our company. Indeed, if we monitor the buffer with the use of a control chart, then the control becomes real insight, the goal of management.

Try it for yourself

Think about your organization. Which process or group of resources might you want to choose as a strategic constraint? The constraint needs to function continuously and smoothly as it dictates the pace of throughput. This means making sure there is enough capacity everywhere else in the organization to make sure the constraint can always perform. An analogy is a surgeon in an operating theatre – everything needs to be organized (resources, materials, procedures) so that the surgeon can focus on performing surgery and not have to worry about anything else. This creates the highest value for the patient.

See Part 9 of this Series ‘Improving Flow Company Wide’

PREVIOUS POSTS IN THIS SERIES:

Radically Improving Organizational Performance – A Systemic Approach to Management Part 1

Leadership for Complex Times – A Systemic Approach to Management Part 5

Working with Variation to Support Good Decision Making – A Systemic Approach Part 7

To find out more about ten guided steps to a systemic leapfor your company, contact Angela Montgomery at intelligentmanagement@sechel.ws

SCHEDULE AN INTRODUCTORY CALL WITH US

Intelligent Management works with decision makers with the authority and responsibility to make meaningful change. We have helped dozens of organizations to adopt a systemic approach to manage complexity and radically improve performance and growth for 25 years through our Decalogue management methodology. The Network of Projects organization design we developed is supported by our Ess3ntial software for multi-project finite scheduling based on the Critical Chain algorithm.

See our latest books Moving the Chains: An Operational Solution for Embracing Complexity in the Digital Age by our Founder Dr. Domenico Lepore, The Human Constraint – a digital business novel that has sold in 43 countries so far by Dr. Angela Montgomery and ‘Quality, Involvement, Flow: The Systemic Organization’ from CRC Press, New York by Dr. Domenico Lepore, Dr. .Angela Montgomery and Dr. Giovanni Siepe.

Leave a Reply