The traditional model for control is the hierarchical model, and the reason for its existence is because personal capacity for control is limited, and adding hierarchical levels increases personal capacity of control. On the other hand, if we want to increase the capacity to listen to the customers and the suppliers, in order to satisfy the needs of the market, we should not adopt a hierarchical model. What is the solution to this conflict?

Hierarchy or non-hierarchy?

How can managers exert control effectively? There is an inherent conflict underpinning the problem of control. The traditional model for control is the hierarchical model, and the reason for its existence is because personal capacity for control is limited, and adding hierarchical levels increase personal capacity of control. On the other hand, if we want to increase the capacity to listen to the customers and the suppliers, so to satisfy the needs of the market, we should not adopt a hierarchical model.

An alternative model

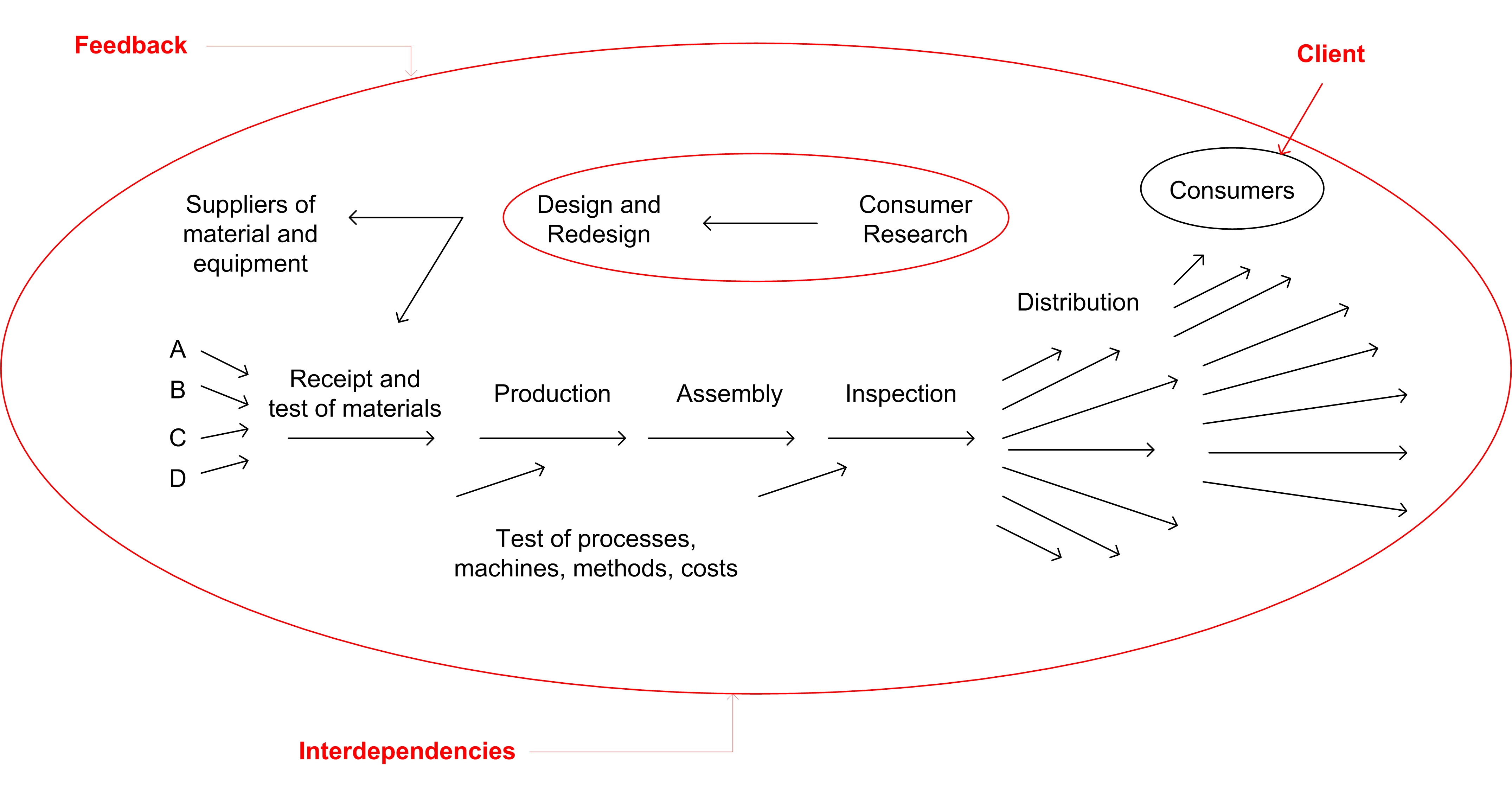

The model we propose, instead, is “the enterprise as a system”, a direct reference to Dr. Deming’s model of “production viewed as a system”:

Deming: Production viewed as a system

The adoption of this model automatically includes in the picture customers, suppliers, and interdependencies, which are completely absent in the hierarchical model. But this approach alone is not enough to manage an organization effectively. The capacity of a system/network of interdependent components to achieve its goal is limited by a very small number of factors, indeed often only one: the constraint.

The constraint as focus and leverage point

Whether you are aware of it or not, every system has a constraint. The constraint is what determines the pace/speed at with which a system generates units of its goal. In for-profit companies the units of the goal are linked to the generation of cash profit (value).

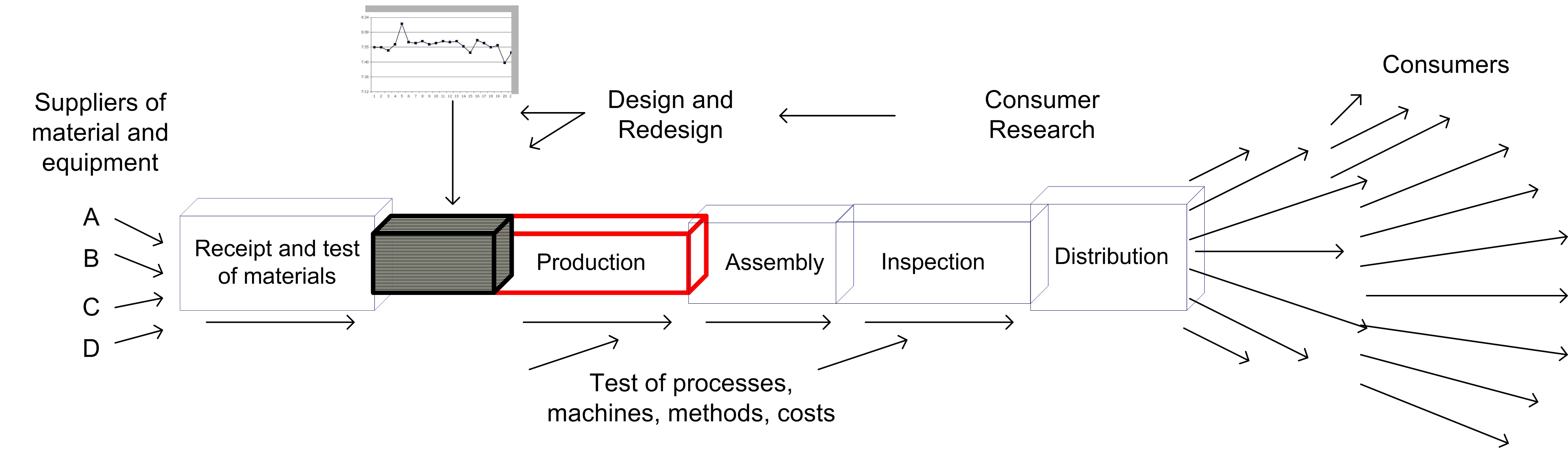

A system that is balanced, i.e. where local efficiencies are pursued everywhere, is highly costly. A system that is instead unbalanced around its constraint is like a tube with one section that is narrower than the rest: there is one phase/process/group of resources with less capacity than all the others.

Why do we manage a system through its constraint? It is because an unbalanced system is simpler and cheaper to manage. In an unbalanced system everything revolves around the constraint phase, and a detailed plan is necessary for this phase only. This schedule allows us to manage the whole plant. Reducing (global) variation in an unbalanced system means concentrating on and investing in the constraint phase only, not every single part of the process.

If we have to manage a plant, then increasing the productivity or improving its performance is considerably cheaper, and less wasteful in terms of time and energy, if it is unbalanced around the constraint. This knowledge is the legacy of Dr. Eli Goldratt, creator of the Theory of Constraints.

The benefit of an unbalanced system

Markets that are stable and repetitive over time, both regarding quantity and product mix, are not very common. That is why following the variation in demand is very difficult. By unbalancing the system around its constraint, we can achieve a flexibility that is much more manageable because the problem of sizing capacity (and making any changes) only concerns the constraint and not every phase of the process.

The algorithm we use to manage production through its constraint is Drum Buffer Rope (DBR). Lead times in plants managed using DBR tend to get close to the time it takes to technically complete the process. This is made possible by eliminating almost completely queues and piles of inventory. Obviously, this short and controllable lead time can become a considerable competitive advantage.

The mechanism to manage a ‘physical’ constraint is, as we said, DBR. The three steps of managing the constraint are:

- Identify

- Exploit

- Subordinate

Identifying the constraint

Identification is relatively simple, since we can very quickly identify the machine, or the process, that limits the capacity of the system. However, considerations about capacity are necessary but not sufficient to identify the constraint. Indeed, in a real plant the product-market demand mix will vary over time and influence the capacity required by the various work centres. It is crucial that, once it has been chosen, the constraint remain the same over time, even when there is an increase in production capacity (“unbalanced” increase). That is why strategic considerations come into play in the identification of the constraint.

The constraint must be chosen bearing in mind that it is the element that determines the speed of cash generation for the whole organization. The main criteria include:

- Assessment of future strategies and scenarios in the market

- Comparative analysis of machines and resources (technical characteristics of the machines, skills of resources, interchangeability)

- Assessment of the investment required and ways of increasing constraint capacity

In our next post we will look at how, on a practical basis, we subordinate the system to the constraint to maximize throughput.

For further information on Intelligent Management’s approach to systemic management see our website www.intelligentmanagement.ws and our latest book ‘Sechel: Logic, Language and Tools to Manage Any Organization as a Network.

Leave a Reply