What is the guiding rule that should inspire any managerial decision? The job of Management is to work on the system and create a predictable environment; as Dr. Deming reminds us “the job of managers is to reduce variation”.

What is the guiding rule that should inspire any managerial decision? The job of Management is to work on the system and create a predictable environment; as Dr. Deming reminds us “the job of managers is to reduce variation”.

Management and predictability

A company is a complex system ruled by non-linear interactions that make it difficult to make any prediction when any change is effected. That’s why any approach to improve the system has to be “holistic”, i.e. address the whole system, and consider all the interactions/interdependencies.

The description of what everybody does, input and output, understanding the interdependencies and, finally, understanding the variation associated with each process, is foundational to any form of “intelligent management”.

What is the guiding rule that should inspire any managerial decision? The job of Management is to work on the system and create a predictable environment; as Dr. Deming reminds us “the job of managers is to reduce variation”.

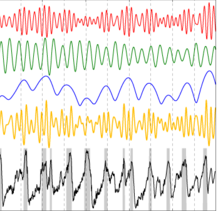

Statistical Process Control (SPC), the main offspring of the Theory of Variation, is the body of knowledge that helps managers to act rationally for the improvement of the system. SPC is not a technique; it is a way of thinking that should be fostered by Top Management at every level in the organization.

The data and the way we collect them are as important as the analysis we perform on them. The starting point to understand the system and its different processes is to select key points where we monitor variation. Once we have identified these points, we can start with the analysis.

Understanding processes

The most practical way to understand processes is to draw a picture of them, by means of a flowchart. A flowchart is a diagram that describes a sequence of events, tasks and decisions that transform input in a process/system into output. Flowcharts use some standard symbols and conventions to make it easier to communicate and understand them and portray a process with a map or chain of activities and decisions.

We can describe the flow of materials, information and documentation; we can show the various activities included in the process, explain how these activities transform input into output, indicate the decisions that have to be made along the chain; we can design interrelations and interdependencies among the various phases of the process that are important, and we can easily acknowledge that the strength of a chain depends on its weakest link.

In describing processes we realize that it is very difficult to establish very precise borders between departments and functions. In order to deliver a product, or provide a service, these fictitious separations are often crossed. We see, therefore, that these processes cut across a traditional organization chart or organization pyramid. Flowcharts are then the key to developing understanding of if, how, and where every single link is adding value to the chain.

Using flowcharts

“…a flow diagram also assists us to predict what components of the system will be affected, and by how much, as a result of a proposed change in one or more components…” (Deming, The New Economics).

What we do is to map out processes and compare them with how they should ideally work, so as to understand where complications lie, identify misalignments between authority and responsibility if any, look for critical points, and determine breakage points in the chain that link the supplier with the customer.

From this analysis we have to recognize ‘Key Quality Characteristics’ (KQC), i.e. aspects of the processes that heavily influence their capacity to contribute to the goal of the system. By highlighting these critical characteristics, we can identify the points where it is more useful to gather data on the variables of the processes. From the analysis of these data we can understand whether the processes are in control (predictable) or not before taking any action to improve them, and whether improvement actions are effective or not.

This post is an extract from the book ‘Sechel: Logic, Language and Tools to Manage Any Organization as a Network’

See also our series on Systemic Management:

Managing Variation: Why Entropy Matters

Why a Software Can Never Manage a Company

Transforming Industry with a Systemic Approach

Managing Projects the Systemic Way: Critical Chain

The Crucial Role of Synchronization in a Systems-Based Approach to Management

Operating a Systemic Organization: The Playbook

Managing a Systemic Organization: The Information System

The Physics of Management: Network Theory and Us

No Fear in the Workplace – Making It Happen

Drive Out Fear by Learning to Think Systemically

Don’t Climb, Grow! Success in the Systemic Organization

Can We Do Away with Hierarchy?

The Network of Projects: Driving Out Fear in the Post-Digital Age

Fear-free Career Paths in the Network of Projects

Learning, Joy, and the Interconnected Future

Structuring the Network of Projects: Algorithms and Emotions

Start Making Sense: Introduction To Statistical Process Control

how you reconcile ashbys view of increasing variety with demings view of reducing variation.

Geoff, the answer is quite obvious,

While variety is a good property when enhancing multidisciplinar approaches, multicultural situations and so on, variation is a different concept.

We understand by variation the results that go away from the nominal value (the point of minimum loses). I recommend you reading Taguchi’s loses curve.

Jordi